Susanna Coffey

- johnwilliammitchel

- Sep 29, 2023

- 9 min read

On a recent grey, chilly afternoon I had the pleasure of meeting Susanna Coffey at her studio on the Lower East Side in New York City. Her studio is in a former school that is now home to artists’ studios, a dance studio, etc. Susanna was one of my drawing and painting teachers at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago in the early 90’s. She has been present in my mind ever since. I’ve attended many of her lectures in NYC since then including talks at the New York Studio School, the New York Academy of Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and others. I’ve also eagerly attended her NYC shows and have a robust collection of her exhibition catalogs. The following interview is a discussion about the work in her upcoming exhibition “Crimes of the Gods” which will include works from the 1980’s, along with recent paintings.

John Mitchell: For your show in May at Steven Harvey Gallery, you're including one of your early large-scale mythological paintings. Talk about that painting and how it relates to the more recent work that will be included in the exhibition.

Susanna Coffey: Where to start? In my artist’s statement for the show I wrote about the confluence of events that led to Rharian Plain, a painting I made in 1998 being included in an exhibition of more recent paintings. Seeing it for the first time in so many years, while also being inspired by the many women and men who came forward to say that sexual predation can no longer be accepted, all these gave me the idea to show this painting alongside new work.

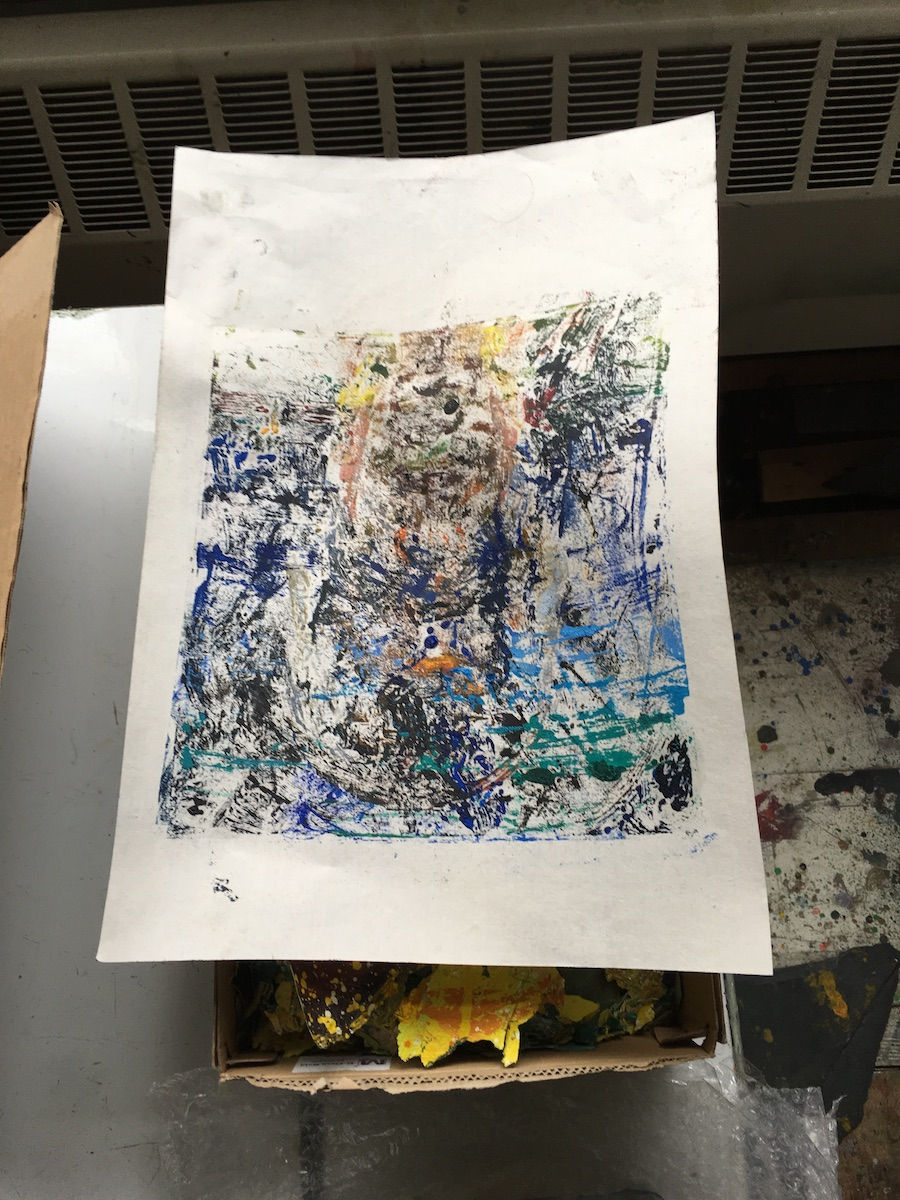

Rharian Plane is one of a group of paintings I made in the 80’s illustrating the ancient Greek classic, The Homeric Hymn to Demeter. After finding the amazing translation of it by Apostolos Athanassakis (to be reprinted this year by Johns Hopkins Press) I kept imagining scenes from the narrative. Thusly inspired I made a series of works based on this tale. It told of gods that conspire, abduct, rape, lie, but finally have to give in to a Goddess’s unshakable commitment to her daughter. In the end all is not perfect, Persephone still has to return to the underworld each winter but each spring she returns to the light of this world.

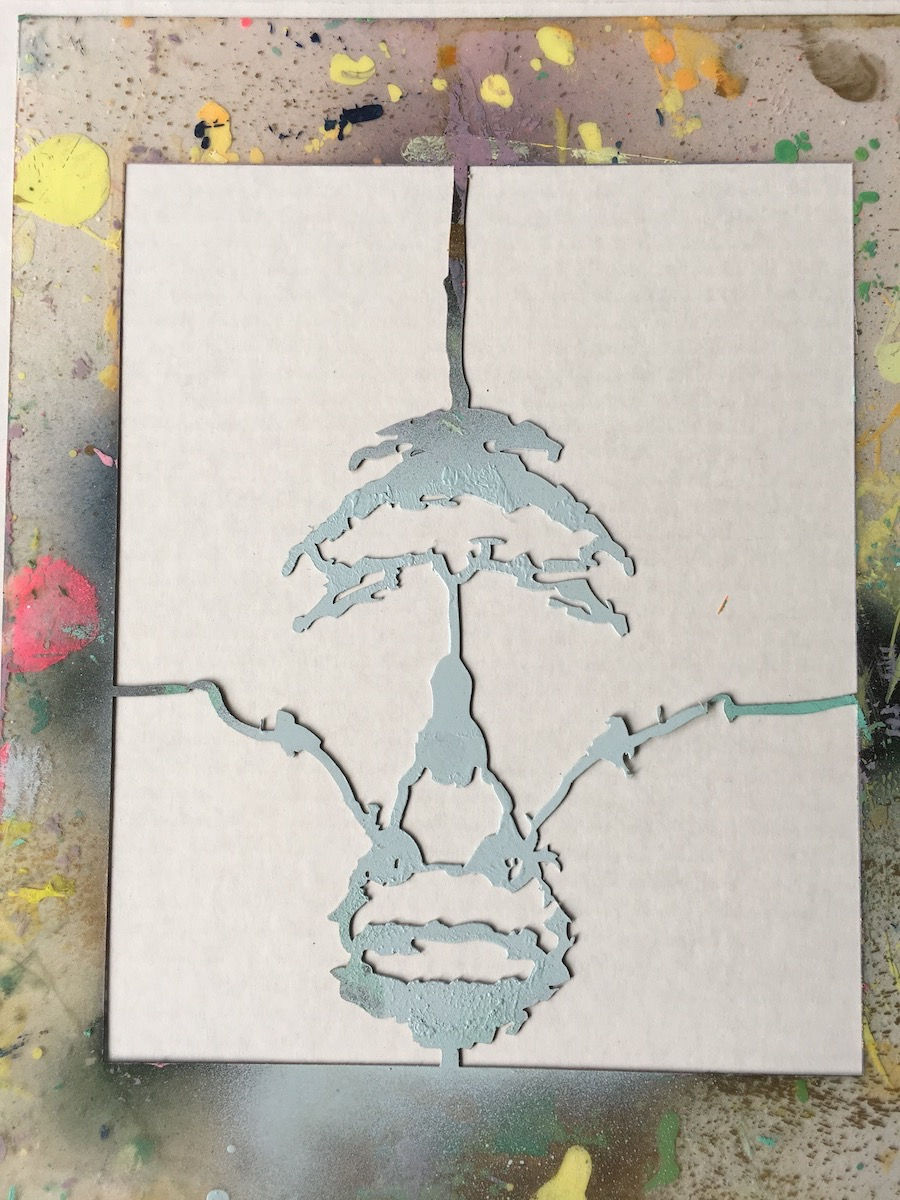

The subject of Rharian Plain is her emergence into Spring, where her mother, Demeter, beckons and nymphs splashily greet Kore’s return to light. In the paintings lower right hand corner one might see another figure submerged in the paint, lying under the green.

I want to show this older work not because I think it is wonderful, but rather that it underscores, for me, a thread that connects all my figurative paintings. In a way I became a figurative painter because of these crimes of the gods and because I feel that one must always envision a return from darkness.

Rharian Plain was painted with that in mind.

JM: When I first saw your paintings at Betty Rymer Gallery at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago as a student in 1993, I remember so clearly the impression of small scale paintings that were at once beautifully textured surfaces made of paint and also brilliant representational images. But I don’t remember sensing narrative in those self-portraits. I think the first time I had a clear sense of narrative in your work was seeing the nighttime war paintings that you started making in 2001. Do you consider your self-portraits to be narrative paintings? How have your feelings about when and how to take on narrative changed since you made the Rharian Plain painting?

SC: The Rymer Gallery exhibition was one of the first times I showed self-portraits. Before then I showed figurative paintings but the source material was my imaginings of literary narratives. The switch in subject matter and way of working was both gradual and unexpected. In 1982 I was hired by SAIC to teach figure drawing and painting but had never, satisfactorily, worked in the tradition of direct observation. If I was going to teach these classes I wanted to understand what possibilities the genre of figuration offered. I had to learn how to paint directly from a motif. So in 1982, as a young faculty, not having much money for models, I began to paint self-portraits from observation in order to be a better teacher. To learn about, not a subject, but rather a process of making, I got a mirror and looked into it and tried to paint what I saw.

At the same time I was making and showing the mostly large-scale works inspired by The Homeric Hymn to Demeter.

As a young painter, I was inspired in a negative way by how few works by women artists, both living and dead, were to be seen. It was clear; the whole world’s visual culture excluded half of the planet’s humans’ artistic expressions. Linda Nochlin’s essay said it all – “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists”. From the very beginning I’ve been suspicious that an art made by only a small slice of humanity can encompass all humanity’s visions. So in the early 70’s my commitment to figurative art was sealed. That same sense of “negative capability” fueled my desire to be a painter. However once I started to paint, I realized how hard it would be to be a good artist. The history was long, great and daunting. But, wow, how thrilling to feel the weight of painting’s history. By second undergrad year, I was committed to painting and also the subject of the problematic of gender. I still am!

Back to 1992-93. After almost ten years of trying to make decent observational work only in order to be a better studio teacher, I finally made one picture that seemed different, seemed complete. Even though it was a “practice painting” I suddenly saw how this motif could fulfill my expressive needs! The mysterious act of seeing, a mask-like face, the vocabulary of a figure-ground relationship, evocative scale juxtapositions, more subtle color relationships, and some things I can’t name, offered me seemingly endless possibilities to show what I felt. It seemed to me each picture could have a theatrical face and that a series of faces could tell the kinds of stories I care about. I imagined a whole group of paintings to be made in front of a mirror and so I made a deal with myself to just go with it. It seemed stupid at the time but I just wanted to see what else that mirror could reveal.

So the Self-Portrait (red cowl) you saw at The Rymer (now owned by Gail Kinn) was the first of what was an unintended but ongoing direction. That picture incited me to envision tales of gender, conditions of personhood, and human presence in a simpler more direct way, while at the same time engaging more and more with the history of painting. The literary/historical inspiration is still there but I feel that the portraits channel them in a more direct way.

JM: When you’re working, do you work on more than one at a time? And when you’re working with an exhibition coming up, do you keep finished paintings out and around while you work on ones that are in progress?

SC: It varies, in this show some recent portraits were backgrounded with paintings from the 80’s. Others, even though they were made before I had this theme in mind, seemed so related. When I brought Rharian Plain into the studio, all the recent works seemed to gather around it and I had ideas for the five newest ones. So for this show I had all the older pictures out while I painted the new pieces. It was all about seeing how past visions related to present ones. Sometimes I do work on one piece at a time but not for Crimes of the Gods.

JM: Throughout the history of self-portraiture, there is a tradition of the painter showing his or herself in the mirror at work, but also showing their palette, as in Diego Velázquez’s “Las Meninas” at the Prado or Judith Leyster’s self-portrait at the National Gallery of Art. In 1997, you participated in a month long “public studio” project at Exit Art on Broadway in SOHO with Joyce Pensato and others. During the run of that project, each artist worked in a big open space and the public was invited to watch the participating artists at work. I remember you had your palette hanging vertically from your easel under your painting. I’d never seen anyone use a palette that way before. How has your working relationship to the palette as a tool and also your preferred color selection evolved over the years?

SC Thanks for reminding me of it, John. The Exit art project Let the Artists

Live was one of the BEST experiences! I loved working alongside all those amazing artists. It was a show in which complete work was present only at the end of the show rather than the beginning. Someone should reprise a few of

Exit Art’s exhibition projects, so many great ideas about how art can be organized for exhibition! Jeanette Ingberman and Papo Colo kept it fresh.

Palettes, what a great question! The palette pre-establishes a painting’s color-feeling, it’s like a musical instrument. I collect photos of and information about artist’s palettes, and love thinking about them, they are like poems to me.

Sometimes I chose a palette for a specific group of paintings. For example, at

Exit Art I wanted to work with Ovid’s description of the ages of man: the Golden Age, the Age of Silver, etc. It occurred to me that some people love the idea of a long-gone, paradisiacal Golden Age and decry as malignant an Age of Iron, which is closest to our present time. For the Exit Art paintings I used an earth palette plus some metallic colors.

Usually I use a lot of colors (about 29) and set them out in a traditional way. I want to be able to make neutral colors as saturated as possible. Chardin inspired me to attempt this. His still life paintings push browns, ochres and grey to full saturation and temperature. A challenge! My colors are arranged like the rainbow, whites and yellows on the lower right, then oranges and reds, purples and blues at the top and moving to the left are greens and then several blacks.

I’ll add and subtract from my usual line-up in response to a painting’s needs.

For example, in Telling I laid out the same colors used in 1988 for Rharian Plain, and included pthalo green and blue. The pthalos can really take over, they are so strong, palette-eaters, I seldom use them.

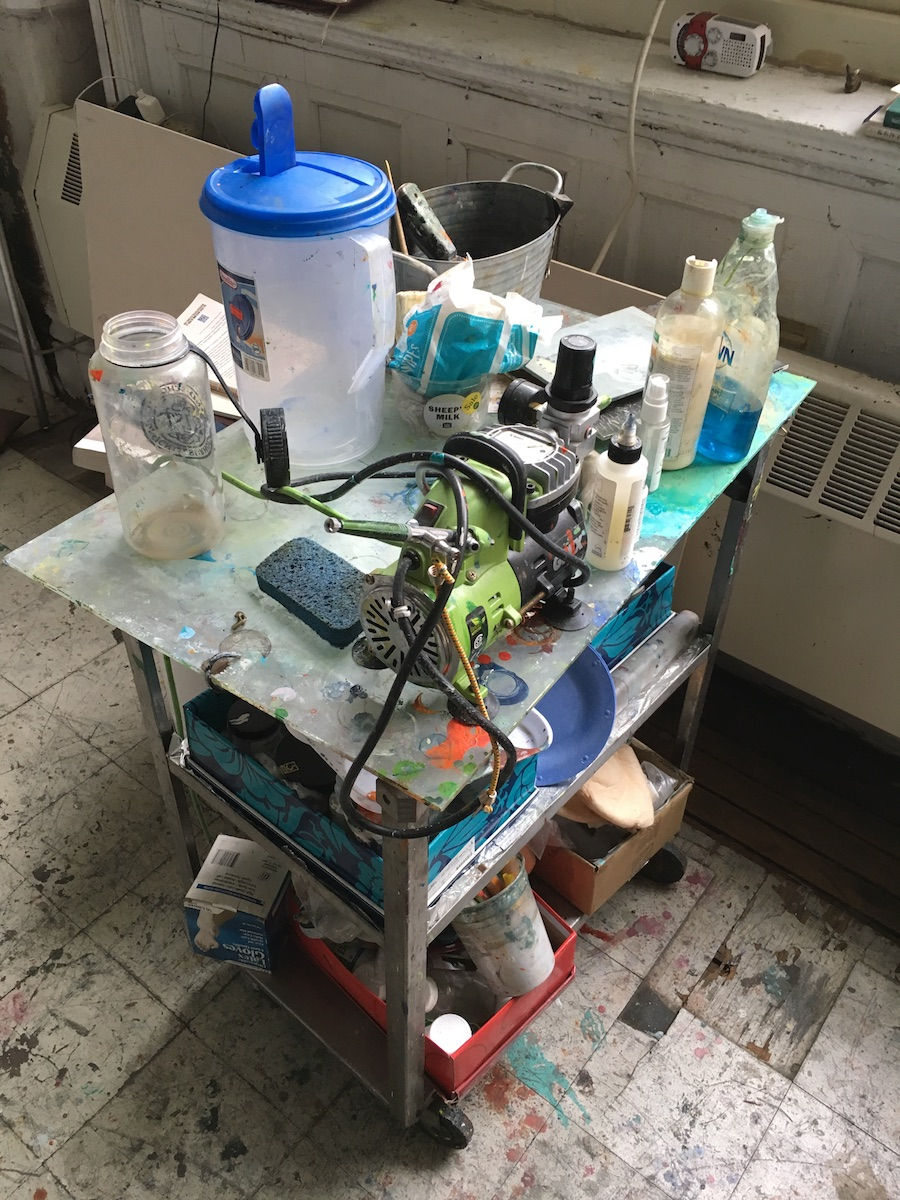

The shapes of my palettes are also important. For self-portraits I need to get as close to the mirror as possible so a very long narrow rectangle works best. I usually have it right under the mirror or the canvas, and yes if I need to it’ll be vertical. I use a smaller squarer one for night landscapes and for still life paintings I use my enameled table’s top. Years ago, when I made the large scale works I used a big palette on a rolling cart along with about five pails of premixed colors wetted with medium and solvent. So I’d adjust (maybe not enough) the premixed colors with the ones on the palette.

One huge influence on my palette was my friendship with Carl Plansky. We met when, in 1990, I saw a dollop of his Cadmium Yellow Lemon on Lisa

Lawley’s palette and knew I’d have to know the person who made this most luminous color. His love and knowledge of paint and its pigments was inspiring and illuminating. His Williamsburg paints were, still are (thanks Mark

Golden), my mainstay supply. I miss our conversations and each time I squeeze out Courbet Green, a staple, I remember his deep knowledge and love of paint itself. And also of his last great self-portraits as Diva! Another is, of course my students, whose struggles to achieve relationship with paint/color have always required me to see/know/consider more regarding color, paint and palette.

JM: Your upcoming exhibition coincides with your retirement from a 37-year teaching career. Throughout that time you have lived and worked part of the year in Chicago and part in NYC. What comes next?

SC: John, this is the question I can’t imagine answering! It’s been over forty years that I’ve been teaching full time. Before grad school I worked in public arts programs, and then I’ve worked at SAIC for thirty-seven. While I’ve been, almost always, tired, not one of those teaching days has been a dull or boring one. I’ve been lucky to work with so many wonderful (mostly) younger people. All along, like so many artists, I’ve tried to keep full attention on studio work. Now as the demands on my time have changed, my vocations probably won’t.

Susanna Coffey’s solo exhibition “Crime of the Gods” opens on Wednesday, May 23rd, from 6-8 PM and will be on view through June 29th, 2018 at Steven Harvey Fine Art Projects located at 208 Forsyth Street, NY, NY, 10002. The gallery is open Wednesday through Sunday from 12-6 PM.

Comments